Ghosts, Orchards, and Borders

Last November, in a post about Bruce Springsteen’s “Highway Patrolman,” I wrote of Nebraska’s palliative effects. I listened to that album without moderation during a hard time in high school. Years later, I listened to another Springsteen album during another hard time. It wasn’t vinyl, as Nebraska was, but a CD I played and replayed on continuous loop every night when I went to bed – Springsteen’s voice always in my head, flattening my grief into something almost smooth. This was just after my grandmother died. She was ninety-one. I was thirty. We’d shared a good stretch of life, but grief is not bound by reason.

My comfort was The Ghost of Tom Joad, an album that confronts and explores the complications of borders. I was at my own border. My grandma – my co-conspirator – had crossed one. Border, as a concept, was deeply felt, albeit in an insular, solipsistic way, and the border songs on this album felt soporific and gentle – despite or because of the misfortunes they exposed. In “Sinaloa Cowboys,” Miguel carries his brother’s body down a swale to the creekside, where Louis died. The last word of that song is “grave.” Miguel “kissed his brother’s lips and placed him in his grave.” I understood that love. That they were cooking methamphetamine didn’t matter. Miguel and Louis worked side by side in the orchards. My grandma and I worked side by side in my grandparents’ orchard. I took what I needed in that song and let it wash over me – the spare, hypnotic voice I heard on “Highway Patrolman” soothing me again 15 years later.

The Ghost of Tom Joad was released in 1995 and won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album in 1997. My grandma died in February of 1999. Though I’d had a few years to appreciate the album on its own terms, Ghost was my soundtrack for the winter weeks after her death, and it would take a few years for me to listen to the album again without loading my own grief into the music. I’m well beyond 1999, but I still love The Ghost of Tom Joad, and am impressed with what Springsteen tackles in his border songs and how those songs (“Sinaloa Cowboys,” “The Line,” “Balboa Park,” and “Across the Border”) feel like corridos.

The Corrido Tradition

Corridos are narrative songs – ballads very much intertwined with the tradition of murder ballads. The earliest recordings of them feature singers accompanied only by guitars. Springsteen adds only keyboard to three of his four border songs on The Ghost of Tom Joad. The fourth, “Across the Border,” includes keyboard as well as backing vocals, bass, accordion, drums, violin, harmonica, and accordion. The addition of the violin, a traditional instrument in a mariachi ensemble, feels like a nod to Mexico, and the inclusion of the accordion feels like a musical acknowledgement of the Norteño tradition.

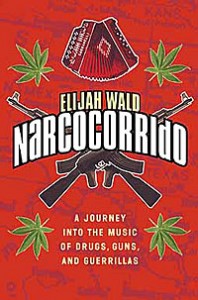

Springsteen’s four border songs on this album feel like corridos because of their narrative quality and their musical simplicity, and because of their narrative subject. As Elijah Wald writes in his book Narcocorrido: A Journey into the Music of Drugs, Guns, and Guerrillas, Mexicans have been writing songs about their border experiences ever since the United States acquired most of northern Mexico in the 1848 treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Wald mentions “El Deportado,” a corrido recorded by Los Hermanos Bañuelos around 1929. That song, he says, is the lament of a deported laborer who came to the United States hoping to find work and escape the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution. More than half a century later, Springsteen wrote his border songs for The Ghost of Tom Joad. These issues remain real and relevant.

Springsteen’s four border songs on this album feel like corridos because of their narrative quality and their musical simplicity, and because of their narrative subject. As Elijah Wald writes in his book Narcocorrido: A Journey into the Music of Drugs, Guns, and Guerrillas, Mexicans have been writing songs about their border experiences ever since the United States acquired most of northern Mexico in the 1848 treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Wald mentions “El Deportado,” a corrido recorded by Los Hermanos Bañuelos around 1929. That song, he says, is the lament of a deported laborer who came to the United States hoping to find work and escape the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution. More than half a century later, Springsteen wrote his border songs for The Ghost of Tom Joad. These issues remain real and relevant.

Wald describes “El Deportado” as a mojado (“wetback”) song because it’s written from an essentially Mexican perspective. By this criteria, most of Springsteen’s border songs are corridos, but not mojados. “Across the Border” is the only border song on the album written from what might be a Mexican perspective.

Continue to page 2>>>

The post Border Ballads: Bruce Springsteen as Corridista appeared first on Sing Out!.