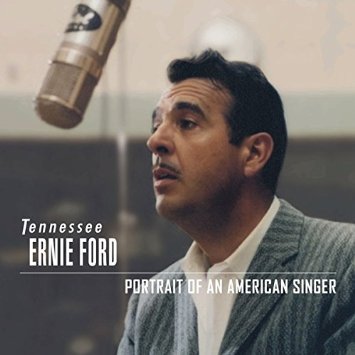

TENNESSEE ERNIE FORD

Portrait of an American Singer

Bear Family 17332

Have you ever felt like – to paraphrase “Sixteen Tons” – you owed your soul to the company store? October 17th marks the 60th anniversary of the release of Tennessee Ernie Ford’s classic rendition, whose populist poetry from Merle Travis’ pen puts it on a par with Woody Guthrie compositions. Commemorating the event, Bear Family Records in Germany has released deluxe five-CD, 154-track Tennessee Ernie Ford: Portrait of an American Singer spanning 1949 to 1960, with a weighty amount of folk music.

Ernest Jennings Ford (1919-91) was born in Bristol, TN, the Virginia/Tennessee-border-straddling town where the Big Bang of American folk music occurred in 1927, when talent scout Ralph Peer discovered both Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family. Ford briefly attended the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music. During World War II, he was stationed in California, married a local girl and later brought her back to Tennessee. But she grew homesick so they returned to Cali, where he worked as a radio announcer, singing along with the country songs he aired, and creating a farm-boy persona, Tennessee Ernie. Meanwhile he moonlighted as a classical vocalist under the name E. Jennings Ford.

His recording career began on Capitol Records with humorous country songs such as “I’ve Got the Milk ‘Em in the Morning Blues,” “Smokey Mountain Boogie,” “Shot Gun Boogie” and baby-awaiting “Anticipation Blues.” His early sessions benefited from an all-star lineup of Capitol studio musicians like steel guitarist Speedy West and guitarists Travis, Jimmy Bryant and Billy Strange. Ford’s fiddler, Harold Hensley, penned his deep-toned 1949 single “You’ll Find Her Name Written There,” which years later Bill Monroe restyled to become a bluegrass classic.

Two trends in 1940s-’50s recordings are clear: pairing male and female singers for duets, and various competing record labels giving their acts the same hit song in hopes of cashing in the song’s popularity. Kay Starr, Helen O’Connell and Ella Mae Morse were among his duet partners. Fond domestic feuding was a frequent theme on these tracks. One of O’Connell’s lines on 1951’s “Cool Cool Kisses” may horrify feminists now.

As for the numerous covers, Ford competed with popster Frankie Laine on “Cry of the Wild Goose.” (penned by Terry Gilkyson, father of Eliza and Tony Gilkyson) and “Mule Train.” Ford once remarked, “While 21 different records were made of 21 different singers singing “Mule Train,” so far as I know I was the only who who’d ever driven a mule.” Whereas Marilyn Monroe sang the theme from her film River of No Return in a quiet, wistful, characteristically breathy style, Ford gave it his full vocal power. When Walt Disney set off a Davy Crockett craze among kids in 1955, Ford, Bill Hayes and the film’s star Fess Parker all recorded “Ballad of Davy Crockett” backed with “Farewell,” and all made Billboard’s top ten. In the tradition of story telling, Bear Family’s Ford box also boasts narrations of Crockett tall tales “The Death Hug,” “A Sensible Varmint” and “Crockett’s Opinion of a Thunderstorm.”

Then we get to his signature song, “Sixteen Tons.” Travis had penned it for his 1947 album Folk Songs of the Hills. By 1955, Ford (a devoted family man) was unhappy that his thriving career kept him away from wife and sons, and he’d been so long absent from the recording studio that Capitol threatened him with a breach-of-contract suit. So on September 20, he did an unusually short two-song recording session, laying down a cover of Ernest Tubb’s 1950 country hit “You Don’t Have to Be a Baby to Cry” and “Sixteen Tons.” It was his first of many sessions arranged by Jack Fascinato – who’d previously been orchestra leader for the beloved “Kukla, Fran & Ollie” program, and who brought Ford a sophistication that his earlier country boogies hadn’t sought. He sagely kept the “Sixteen Tons” arrangement minimalist, which accentuated the lyrics and vocal. Listen to Ford linger on the first word, “some.” Beatnik-like finger snapping and discreet reed and trumpet later enter. He closes the song with slow melismas on “I owe my soul to the company store,” a line Travis’s father, a coal miner, had frequently uttered.

Fascinato used a similar approach on Ford’s first LP, This Lusty Land (1956), a folk venture including “The Rovin’ Gambler,” “Who Will Shoe Your Pretty Little Foot” and Travis’s compositions “Dark as a Dungeon” and “Nine Pound Hammer” (both of which he’d penned for Folk Songs of the Hills). Borrowing from his classical background, Ford gave“In the Pines” a formal treatment that its variants hardly got from Lead Belly, the Louvin Brothers or Nirvana. The next year on Ol’ Rockin’ Ern, Ford re-recorded some of his country boogies – all but one from his own pen – using similar arrangements (which rocked less than his original versions). In 1959, Gather ’round Tennessee Ernie Ford (again with Fascinato) reflected the growing folk revival with the likes of “Barbara Allen,” “Freight Train Blues” and “Brown’s Ferry Blues.” On “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair,” his operatic training is obvious, recalling the ballad’s delivery by collector John Jacob Niles, who here is credited with its authorship.

Essentially, Ford was blessed with perfect matches with two long-term producers: Cliffie Stone for the country boogies and then Fascinato for sessions that relied heavily on what would eventually be called Americana music. We hear it all on this near-sixteen-ton box, which includes a 174-page hardbound book offering biography, sessionography and photos galore. Except for his three high-selling gospel albums (which are already on CD), here’s his entire studio output. over a 12-year period. Judging by the biography, there’s a reason why his tracks sound so congenial: That’s how he genuinely treated people.

— Bruce Sylvester

The post TENNESSEE ERNIE FORD: Portrait of an American Singer appeared first on Sing Out!.